Why Do We Want Public APIs? (Android Intents Part 2)

This is the second post in a series about sharing information between apps. (Part 1 is here.) In this post, we’re going to discuss why it might be nice to have a public API exposed from a third party app. I’ll be providing videos that cover the text contents of these posts (plus insightful things), so if you want to watch instead of read, check out the video below:

If you watched the video, feel free to skip to Part 3, where we’ll look at some code. This post is simply a text version of the video.

Series Table of Contents

Follow the series on the Table of Contents page.

Why do we want a public API on the phone?

There are three perspectives here, the user is one, and then the producing developer, and consuming developer are the other two. This isn’t as complicated as it sounds.

I’m going to put this in terms of a couple of concrete apps, so that we have some apps that we can look at, and think about, as opposed to talking so much in the abstract. We’ll talk about MyFitnessPal as the producing developer, offering the API. Strava and Withings will be the consuming developers, they consume MyFitnessPal’s APIs.

This discussion may seem kind of long, but it is the central idea of this entire series. I promise we’ll get back to code soon. Again, if you watch the video, you can skip straight to Part 3, because all of the long text part is covered in the video.

I’d also like to mention up front that these apps already do integrate with each other, but they do it via the web, not on the phone. I’ll discuss the difference in the ‘user’ section. There’s also Google Fit, which intends to take care of this particular issue, and IIRC provides some useful integrations on the device side. In short, this particular example is almost completely solved already, but it’s an easy one to think about, so we’re going to keep it.

Producing Developer

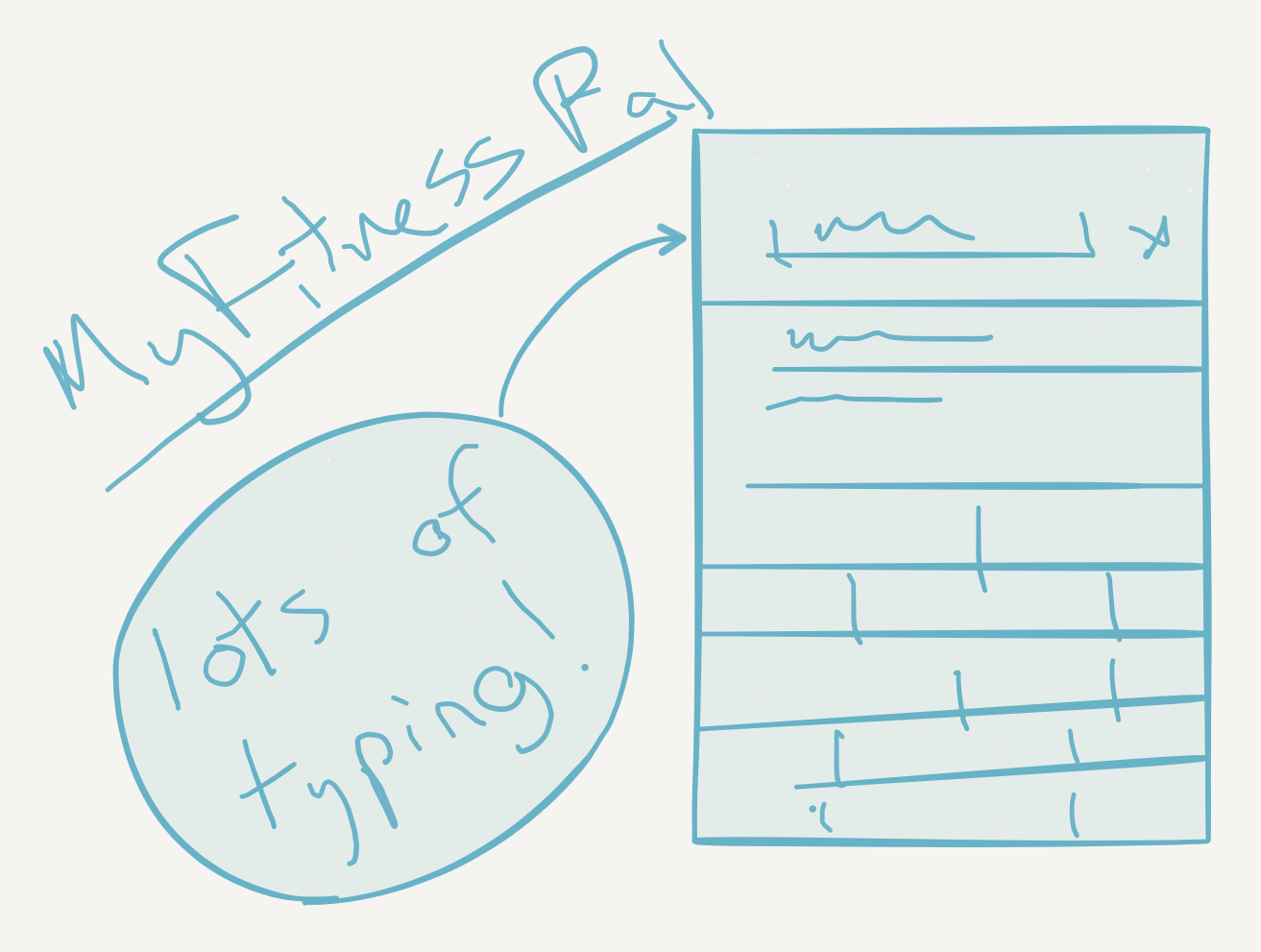

MyFitnessPal, lot’s of typing!

Imagine that you’re MyFitnessPal, and an app that does calorie counting. MyFitnessPal provides users a way to enter their food and exercise and your app tells them how many calories they’ve consumed and how many they’ve burned. Now, you care about gathering fitness data from users, but your main method of getting that data is asking users to enter it manually. Then, along comes Strava, they do automatic tracking for bicycle riding and running. If your user is using both Strava and MyFitnessPal, you could open up an API for Strava (and any other activity tracking app) to send data to MyFitnessPal, so that users don’t have to manually input something that was already captured automatically for them.

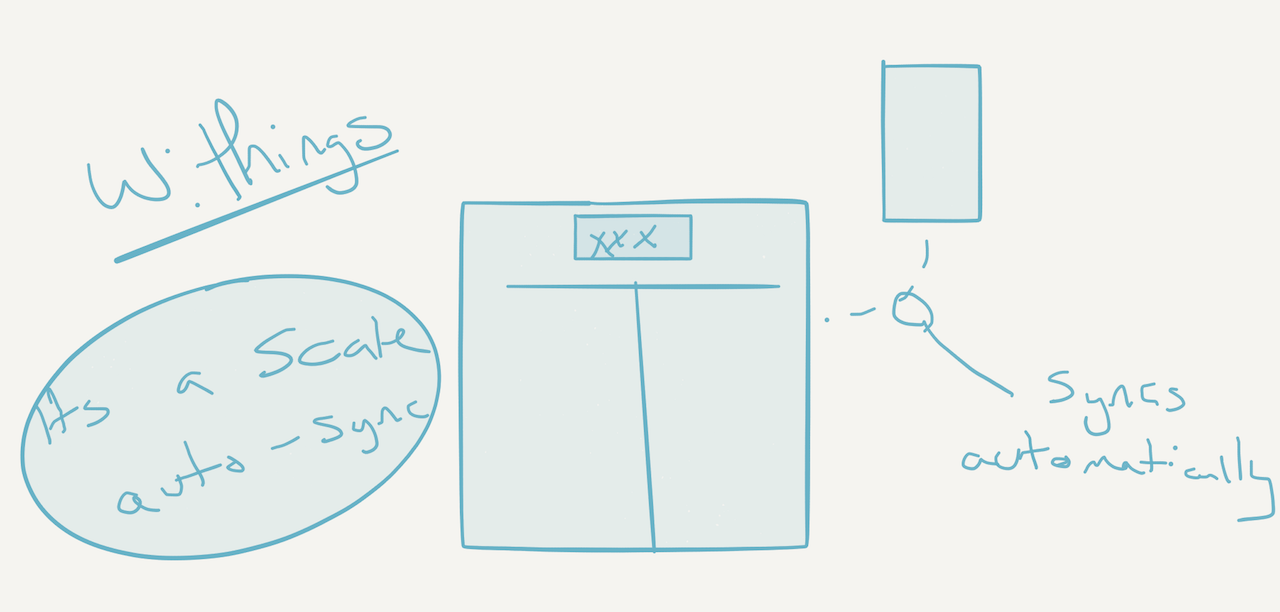

Withings, works just like an ordinary scale, but it syncs your weight to its service

It’s the same deal with Withings, they provide some passive tracking hardware, like a digital scale that sends your current weight to their app, an activity tracking watch, as well as some other products. You, as MyFitnessPal, could open another API that would allow Withings to sync up the user’s weight with you. Withings could use the same APIs for exercise tracking that you opened up for Strava.

The apparent downside is that users will no longer need to enter your app to manually enter this data. However, by offering an API for other apps to consume, you’re actually making both your app and the other app more powerful. Now the user needs to do less work, and they’re going to appreciate that they get stuff for free (free data entry, which is a pain to do on your phone). When you start offering APIs that other apps can consume, users are going to like you more because make the their life easier.

Consuming Developer

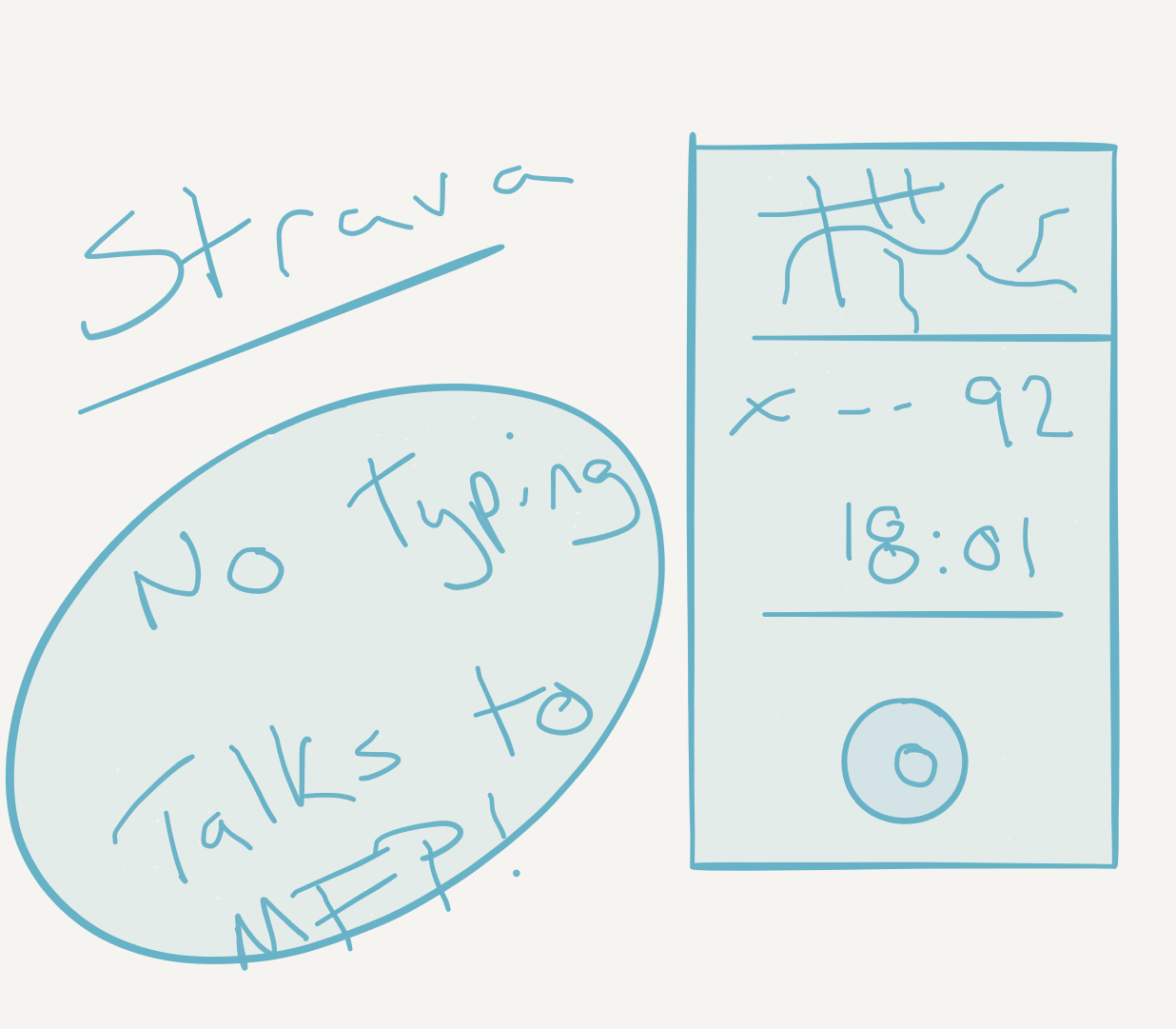

Strava doesn’t require much typing, it records your session.

Now, imagine you’re Strava, you do a great job tracking users’ runs and bike rides, but your users are asking for food tracking as well. That’s a difficult problem, and not really your core competency. It’s something that you really don’t want to do yourself. Luckily, you know that MyFitnessPal does food tracking really well, and they also do exercise tracking. What’s more, they offer an API that allows apps like Strava to send them activity data. All you need to do is implement an API, and now you can tell users to install MyFitnessPal when they ask about food tracking. The best part is that it’s automatic and in the background, users don’t need to think about it, and you’ve done almost no work. It’s a win-win!

User

Imagine that you’re a user that wants to count calories, track your weight, and goes running. MyFitnessPal, Withings, and Strava all work together to allow you to do most of this tacking passively, cutting down the amount of manual data entry you have to do, and saving you time. If there’s a run tracking app that you like, but doesn’t integrate with MyFitnessPal, is that extra friction worth it, or are you going to switch over to Strava?

As I mentioned before, these apps already do integrate with one another, and it’s not exclusive to the listed apps, most of the worthwhile fitness apps I’ve come across integrate with each other. The one big downside is that they integrate in the backend, not on the phone. What this means is that users need to sign into different services multiple times on their phones, or set up those integrations on their computers. This is friction. Why not just do it seamlessly on the phone? Is there a reason to even ask the user to log in, when they’re already logged in on the phone in the other app?

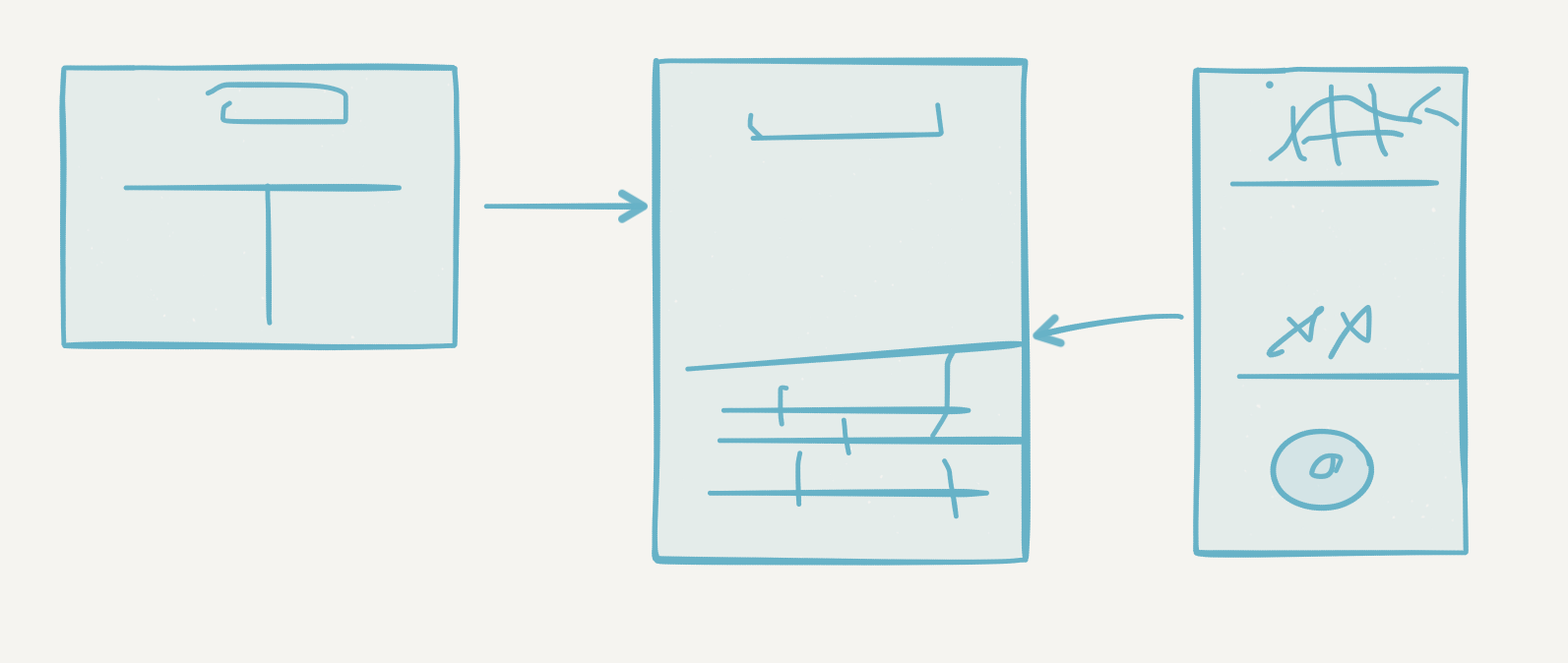

Instead of integrating on the backend, it seems possible to integrate on the frontend. The apps just fire intents at each other, and allow the providing app to do the auth in their app. This could be as simple as popping a dialog and asking the user if it’s OK if the other app send it data. What’s more, it means that you don’t need an internet connection for the apps to sync with each other (either via intents, or maybe a combination of intents and content providers). Currently, these services sync up on their own schedule, and it can cause users to manually enter information that will be automatically synced later. Friction.

The above is a sketch of Withings and Strava talking to MyFitnessPal, if you couldn’t tell. =)

Conclusion

In this post I explained why we’re bothering with this whole exercise. We discussed a real-world example of how this sort of thing is helpful to all parties, users, API providers, and API consumers. Hopefully this has given you some perspective on what this series is all about, and where we might want to go from here. Incidentally, if you have ideas for this series, please feel free to reach out.

Next time, we’ll look at an example that demonstrates a fun way to both produce and consume a public API on the phone.